What the Mac Has Learned About Security from iPhone and iPad

Caleb Basinger

Caleb Basinger

Mac users have long enjoyed the platform’s open approach to computing. There was an exposed file system, no limitations on how many apps you could run at once, and scripts that took action when triggered by events. The only barrier to doing whatever you wanted was when the OS crashed or became unusable. The openness of the platform gave users and IT administrators alike plenty of flexibility.

Then iOS came along. Because Apple was able to start fresh with iPhone OS (before it became iOS), because the mobile operating system was built from the ground up and didn’t have to worry about backward compatibility, the company was able to build a security model into iPhone and iPad devices that was forward-looking and designed for an environment in which connectivity was constant and security threats were pervasive.

Both iOS and iPadOS were restricted in ways that rankled many users accustomed to the more open Mac. Apps could only come from the iOS App Store. For many years, those apps couldn’t run in the background; when they finally did, they could do so only with limitations. And for a long time, the file system wasn’t exposed.

Apple designed iOS and iPadOS this way because it was more stable and secure. Though power users loved the freedom they had on the Mac, even they had to admit that iOS was more streamlined and harder to break.

But over the years, the Mac has been changing. You can still install your own apps, but they should be notarized with Gatekeeper. IT administrators can still manage Mac computers, but they must use Apple’s official APIs. For many years, iOS was seen as a baby sibling to macOS. But if you zoom out, you can see that, when it comes to security and IT-friendly enhancements, macOS has been taking its cues from iOS.

The Evolution of Mac Security

If you just look at a little Apple history, it isn't hard to find the persistent pattern of security features migrating from the iPhone and iPad to the Mac.

App Store and Sandboxing

The opening of the first iPhone App Store in 2008 launched the mobility revolution. Sure, there had been third-party apps for Blackberry, Palm, and Windows Mobile. But the iOS App Store became a cornerstone of the iPhone and iPad platforms, the place where you could get trustworthy new apps with just a few taps.

In 2011, the App Store model came to the Mac. It made installing apps—purchased and managed via Apple Business Manager’s Apps and Books system—a seamless experience for users and admins alike. Depending on which device management solution you use, you might be able to install non-App Store apps through it, too, but the infrastructure for installing apps from the Store is easier by far. And that makes installing apps from App Store more secure, too, thanks to sandboxing.

![]() From the day iPhone OS first launched (with the iPhone SDK in 2008), apps were sandboxed. That meant they were strictly limited in their access to other applications and system resources. Even Apple’s own apps had to play by these rules. With the advent of the App Store, that same approach to software came to the Mac.

From the day iPhone OS first launched (with the iPhone SDK in 2008), apps were sandboxed. That meant they were strictly limited in their access to other applications and system resources. Even Apple’s own apps had to play by these rules. With the advent of the App Store, that same approach to software came to the Mac.

The sandboxing requirement is why many popular enterprise apps—including Microsoft Office—were not available in the Mac App Store for a long time; their developers hadn’t refactored them to operate in a sandboxed environment. But now there are plenty of apps engineered to play nicely in the Mac sandbox. Over the years, big developers have found ways to sandbox their apps. Sometimes the functionality of the sandboxed app might differ from its unboxed equivalent; that’s the case with Microsoft Word, Powerpoint, and Excel, for example. But vendors have realized that—just as many of them did when working on iOS apps—they had to adapt to sandboxing if they wanted to maximize their chances in the Mac market.

System Integrity Protection

System Integrity Protection (SIP) sets critical components of the operating system to read-only and stores them in specific locations, to keep malicious apps from modifying them. It was baked into iOS from the very beginning but only came to the Mac back in 2015 with OS X El Capitan. It’s been on by default ever since.

When SIP was originally introduced, many power users in the Mac community thought it was the beginning of the end. While it can cause some difficulties for certain low-level applications, SIP has been overall a big security upgrade for macOS. It can be disabled if needed, but that’s not recommended. The vast majority of end-users have no idea of what SIP is or that it’s enabled on their computers—which is probably the correct model when it comes to fundamental security.

APFS

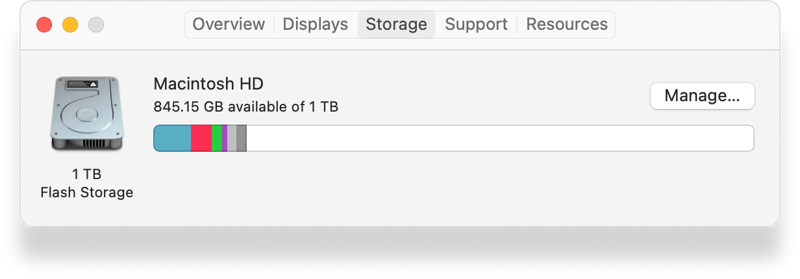

When Apple released the Apple File System (APFS) in 2017, the Mac and iOS community was amazed that Apple was able to transition to a completely new file system so seamlessly, without needing to wipe entire systems. And when APFS was released to the Mac in macOS 10.12.4, it set the stage for one of the biggest feature enhancements for Apple IT administrators: Erase All Contents and Settings.

Prior to APFS and Erase All Contents and Settings, a storage device would need to be formatted and macOS reinstalled from scratch to ensure that a drive was free of personal information. With Erase All Contents and Settings, a single command from a device management system can completely erase personal data from macOS without requiring a reinstall of the OS. For organizations decommissioning dozens of Mac computers at a time, this protects personal data while saving hours of admin time.

TouchID and Biometric Security

Touch ID came to the iPhone with the iPhone 5S; it was the first time biometric security became widely used on mainstream personal devices. While some PC laptops had included fingerprint sensors, Apple’s implementation was reliable, easy to use, and protected your data. One of the first things Apple highlighted with Touch ID is that the encrypted hash it generated stayed on the device and wasn't accessible from iCloud or any other cloud service. It evolved into Face ID on iOS, but it maintained the same level of security.

Apple eventually brought Touch ID to the Mac, allowing end-users to unlock their devices, purchase apps, and authenticate new apps for installation using just their fingerprints. Apple designed Touch ID on the Mac with the same security as iOS: Its data stays on the device, isn’t synced to the cloud, and isn’t accessible to IT administrators in their mobile device management system.

Would it be easier for end-users if their Face ID and Touch ID settings were synced over iCloud to all of their devices? Sure—but it wouldn’t be as secure. When a device is wiped, all aspects of that person’s biometric data is wiped with it.

Secure Enclave

Finally, there’s Secure Enclave. It’s part of the system on a chip on Mac computers with Apple silicon; the T2 security chip enables it on Intel-based Mac computers. It’s designed to protect the most sensitive data, such as the biometric information discussed above.

It took Apple a while to bring this core functionality from the iPhone and iPad to the Mac. But with Apple silicon now in place on the Mac platform, it’s clear that Apple’s master plan all along was a system where the company could implement the highest level of security to keep sensitive user data secure—even when the application processor kernel became compromised.

The Lessons for Mac Admins

Apple has long maintained that macOS and iOS are not merging. But it’s clear that Apple is not afraid of bringing features from one platform to the other. As we’ve seen, it’s been migrating the best parts of iOS and iPadOS security to macOS in a way that lets the Mac be the Mac while also making it more secure. Just as iOS has become slightly more open in ways that don’t impact security, macOS has become more secure in ways that don’t compromise its openness. As Apple continues to refine its platforms, you can expect that trend to continue.

Which brings us to the realm of device deployment and management: In an era when admins still relied on network directories and on-premises policy servers, Apple taught an entire industry how to radically reimagine the deployment and management of devices through a mobile-first lens.

Enrolling devices with account settings, applying appropriate restrictions, and pushing apps and content became a breeze with iPhone and iPad devices. And that paradigm easily extended to the Mac, when the vast majority of Mac computers sold now are mobile.

But knowing the unique openness of the Mac, Apple has thoughtfully balanced the ease and security of its MDM protocol while still allowing device management vendors to extend MDM features with their own agent software.

We should expect to see Apple move device management more and more into the sandbox of its MDM protocol but in a calculated way. The company has always kept one eye on the jobs of a Mac admin and the other on security—with a hand extended to protect the privacy of end-users. The security of all of Apple platforms will continue to evolve and disrupt—and admins and users will both be the better for it.

About Kandji

The Kandji team is constantly working on solutions to streamline your workflow and secure all of your Apple devices. With powerful and time-saving features such as zero-touch deployment, one-click compliance templates, and plenty more, Kandji has everything you need to bring your Apple fleet into the modern workplace.

See Kandji in Action

Experience Apple device management and security that actually gives you back your time.

See Kandji in Action

Experience Apple device management and security that actually gives you back your time.